The seventh starling (Murmuration)

What do particle physics, statistics and poetry have in common? (includes videos)

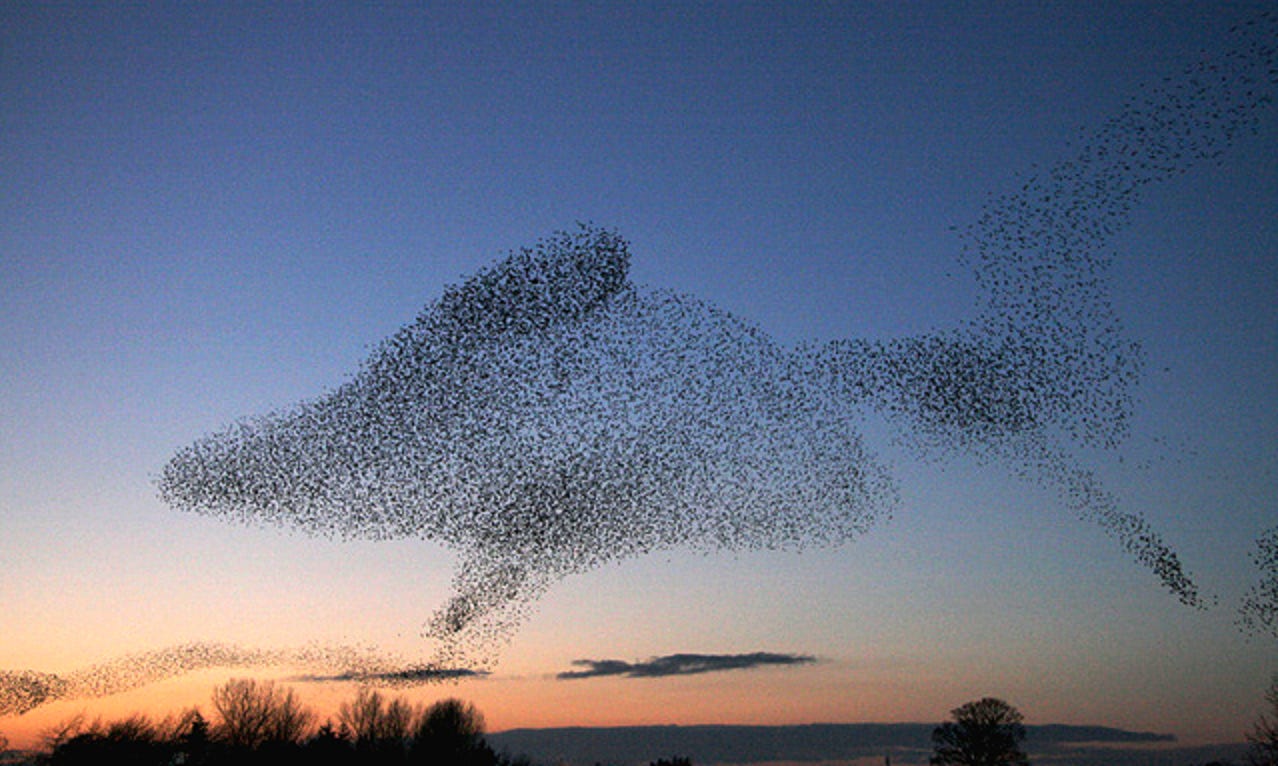

Starling shapes in the evening sky

A large number of starlings congregate at Gretna Green every evening at sunset during the winter months to perform an elaborate aerobatic display before roosting in nearby conifer plantations. It can be quite breathtaking to witness the birds twisting into unusual patterns in the sky. (© Copyright Walter Baxter and lice…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Words About Birds to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.